Pro Tips

Why Doing Less Can Actually Strengthen Your US University Application

Jan 26, 2026

The Myth of “Doing Everything”

Many students applying to US universities believe the safest strategy is to do as much as possible. Join multiple clubs. Try every competition. Add a new activity each year. The result often looks impressive on paper, but rarely convincing to admissions officers.

In reality, US admissions teams are not counting activities. They are reading for direction, depth, and narrative coherence. Students who try to do everything often struggle to explain why they did any one thing meaningfully.

What US Admissions Officers Actually Look For

In conversations and public panels, US admissions officers repeatedly emphasise the same idea:

they are far more interested in sustained engagement and growth than in short-term participation.

A commonly echoed sentiment from admissions teams is that:

a student deeply committed to a small number of aligned activities is often more compelling than one who dabbles across many unrelated ones.

This is because US admissions is not just about capability—it is about trajectory. Officers want to understand how a student’s interests developed, how they acted on them, and where those interests are heading.

Depth Beats Breadth, But Only If It’s Intentional

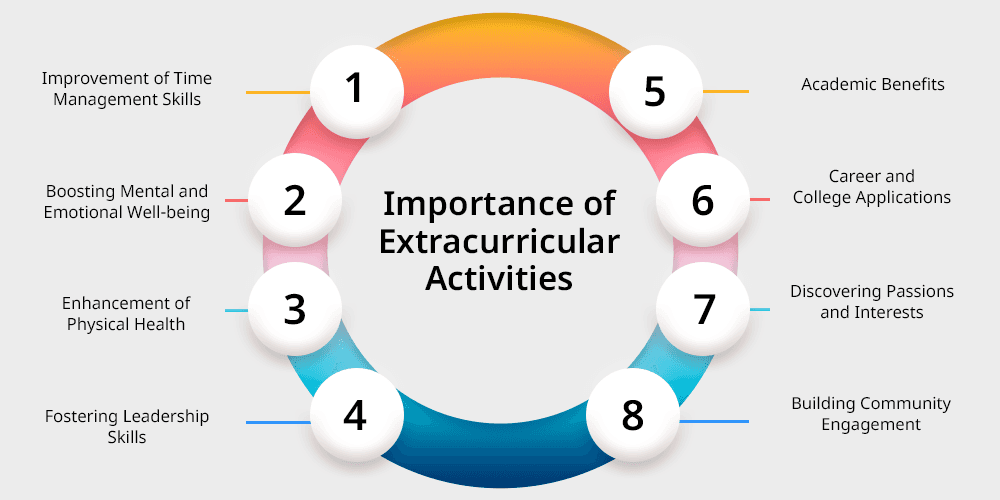

This image represents sustained involvement rather than surface-level participation. US admissions officers look for evidence of progression—students who stay with an activity, take on responsibility, and deepen their impact over time, rather than those who join many clubs briefly without direction.

This does not mean students should avoid extracurriculars like Model United Nations, sports, or volunteering. These activities can be valuable. The issue arises when they are pursued without direction or continuation.

For example:

Joining MUN for one year, attending a few conferences, and then dropping it adds limited value.

Staying in MUN over multiple years, taking on leadership, specialising in certain committees, or linking it to a broader interest in international relations or policy tells a far stronger story.

The same principle applies to every activity. US universities reward progression, not experimentation for its own sake.

A Flyers Student Example: Building a Coherent Story

One Flyers student applying to US universities for Computer Science initially planned to join everything available—MUN, debate, coding club, volunteering, student council.

Instead of spreading effort thin, we helped them make deliberate trade-offs.

They chose to:

Prioritise hackathons and coding competitions

Take on a leadership role in the maths and computing society

Build independent coding projects over multiple years

Document learning through online courses and applied problem-solving

They did not continue MUN beyond a short exposure year. Not because MUN is “bad,” but because it did not reinforce their academic direction.

By the time applications were submitted, the profile told a clear story:

a student who explored computer science deeply, took initiative, grew in responsibility, and demonstrated commitment over time.

That clarity mattered more than the number of clubs listed.

The Trade-Off Most Students Avoid Making

Every strong US application involves trade-offs. Time is finite. Energy is finite. Admissions officers know this.

What weakens applications is not a lack of activities, but a lack of focus:

Too many one-year commitments

No visible progression or leadership

Activities unrelated to the intended major with no explanation

US universities are not asking, “Did this student do everything?”

They are asking, “Does this student know where they’re going?”

Direction Matters More Than Popularity

Certain activities—MUN, student council, generic volunteering—are extremely common. This does not make them useless, but it raises the bar for how they are presented.

A computer science applicant who spends one year in MUN and cannot connect it to their academic interests gains little. The same applicant investing years into technical projects, competitions, and leadership within subject-relevant spaces sends a far clearer signal.

The key is not prestige. It is alignment.

How to Think About Activities Strategically

A strong US-focused extracurricular strategy usually follows three principles:

Select a small number of core activities aligned with academic interest

Stay with them long enough to show growth, leadership, or impact

Be able to explain why each activity belongs in your story

This approach does not make applications narrower. It makes them sharper.

Final Thought

US universities are not impressed by students who try to be everything at once. They are impressed by students who show intentional growth in a clear direction.

At Flyers Academy, we help students stop chasing checklists and start building narratives—so every commitment has purpose, progression, and credibility.